“Refugees are mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, children, with the same hopes and ambitions as us—except that a twist of fate has bound their lives to a global refugee crisis on an unprecedented scale.”

— Khaled Hosseini

On September 1st 1939, Hitler invaded Poland from the west, and on September 3rd Britain declared war on Germany, starting World War 2 in Europe. It was a war which would last 6 years until September 2, 1945. In Trinidad, there were prayers for peace, but once war was declared the man on the street erroneously assumed the war would be a European affair (deVerteuil, 2014). Trinidad’s oil refineries made it an asset to the war effort, and this meant it could be considered a target for any German attack. By the time the war broke out there was already a small number of Ashkenazi Jews in Trinidad who migrated for economic reasons in the early to mid-1930s from South America, Colombia, Curacao, Venezuela and Honduras (deVerteuil, 2014). These Jews were to play an important role in helping the war refugees in Trinidad.

During World War II, the displaced and persecuted desperately sought refuge anywhere and Trinidad became one of these places of refuge due in part to its early-war apathy on the part of legislative officials and the general public. Trinidad became an unexpected shelter to refugees fleeing persecution in Germany as the country did not require a visa for entry, had “relatively lax immigration laws” and was part of the British Empire (deVerteuil, 2014). Many of the refugees had never heard of Trinidad before getting onto the ships from Europe. One refugee David Lapscher is recorded as saying:

“My father left Bessarabia heading for Honduras only to be told in Amsterdam, where he was to board the ship, that the immigration to Honduras was closed and when told that Trinidad was open he replied ‘well that’s where I am going’.” (deVerteuil 2014, 143)

The Trinidad colonial government responded to the war and influx of visitors by issuing regulations reducing the number of patrons at any public gatherings to nine persons until the end of the war and implementing an ‘Alien Registration Order’. According to deVerteuil (2014, 156) “this order required all aliens from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Danzig to present themselves at Police Headquarters with passport and recent photo in hand to register as enemy aliens, and were to be prohibited from possessing any arms, ammunition or explosives, photographic equipment or motor vehicles and were prohibited, also, from leaving their homes for more than 24 hours at a time”. Unfortunately, they were escaping persecution in Europe only to be met with economic and social troubles in Trinidad. “Once the war started it began a downward psychological and economic spiral for the Jews on the island – peddlers unable to leave the city to sell and collect debts, tourists disappearing, German and Austrian Jews laid off from commercial firms.” (deVerteuil 2014, 157)

While the history of WWII refugees as well as the Jewish experience in the Caribbean -especially how they managed to end up here – is a fascinating one, this article explores a small part of the history of the refugee experience during the time of the World War II after their arrival to Trinidad, the internment experience and the places and spaces that are now part of Trinidad’s cultural landscape and heritage.

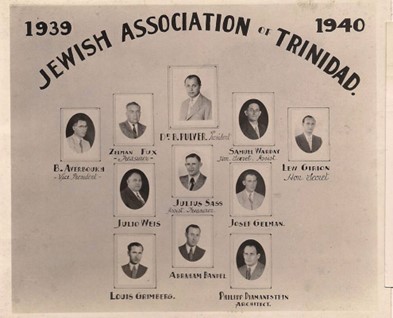

Jewish Association of Trinidad poster.

Source: https://ttao.ca/news–info/jewish-association-of-tt

The Internment

The declaration of war on Germany by the United Kingdom fundamentally changed the nature of immigration in the colonies, including the colonial West Indies. The estimated number of refugees to the insular Caribbean in the context of World War II ranges from at least 24,000 up to 28,000 refugees (Cwik and Muth 2017). Trinidad, Jamaica and other British controlled Caribbean territories began to see a massive influx in refugees. In many cases, the location of the Caribbean encouraged refugees to make use of these islands as stepping-stones to North American and South America (Cwik and Muth, 2017).

Immigrants from countries at war with the UK were designated “enemy aliens” in the British, Dutch, French and US-American colonies, and territories. There was clear discrimination as this included Jewish refugees from Germany as well as the Austrians and select territories occupied by Germany, who were absorbed within the group of Germans as “German-speaking” (Siegel 2003, 16). In Trinidad, all Austrians, Germans and Italians in 1940 were detained by the colonial government but not the stateless from Danzig or Czechoslovakia or those with Romanian or Polish passports. Governors of the colonies were advised of a decision to intern all male “enemy aliens” between the ages of 16 and 60 and on June 21st, 1940, the Jewish refugees were informed of the government’s decision to institute forced detention in the form of internment (de Verteuil, 2014). Postal cards were sent in the mail requesting they present themselves to the Police Headquarters and by August 1st general internment was complete.

It would not be until July 1941 that the Secretary of State for the Colonies would instruct Governor Young to release the internees. By September Trinidad’s General Council agreed, and releases began in October of that year. Lamentably, it took three and a half years before the last Jews were released in January 1944 and the internment camp called Camp Rented was closed, thus ending the period of internment (de Verteuil, 2014).

Sign on Nelson Island acknowledging the presence of the internment camp for refugees during the Second World War. Source: Kara Roopsingh 2020

Remembering the refugee experience through heritage sites

Nelson Island and Caledonia Island

Caledonia Island and Nelson Island, of the Five Islands, were used as temporary internment camps during World War II. Governor Young designated Nelson Island as the temporary detention centre in 1939 prior to the start of the internment. Nelson was also previously used for many years as an immigration depot for Indian immigrants who required medical examination and subsequent assignment to Estates in Trinidad. Therefore, when the need arose for it’s use as an internment camp, many structures were already in place and swift renovations took place with some outbuildings added. This mirrors sleeping arrangements outlined by Indian immigrants during the island’s use as a convalescence station in the 19th and early 20th century (Morris, 2019). “Due to the small area and large continually increasing numbers, the sense of confinement on Nelson was extreme” (de Verteuil 163, 2014). Much of the structures developed for both the immigration depot and the internment camp remain today and can be viewed upon a tour of the island through the National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago which manages the island. The island is also a protected national heritage site or listed property of interest protected by law.

For the internees in 1940 “Life on the island was restricted to a daily routine of chopping wood, cooking and cleaning, talking and reading and playing cards under the watchful eyes of wardens…swimming (once a day) and fishing were permitted.” (de Verteuil 162, 2014). The Men and older boys were kept on Nelson Island and four weeks later the women and young children were placed on the adjacent Caledonia Island.

“Some gazed across to Nelson, where in the shade of the leafy Matapal tree, Tubal Uriah Buzz Butler, the riotous Grenadian-born labour leader, sat sedately in his rocking chair stroking his long beard and quietly oscillating his large fan. Butler was considered a danger to the state during the war and remained confined in Nelson for the duration of the conflict” (de Verteuil 163, 2014)

This would not be for long, as one month later Camp Rented was built on the mainland and all the internees were relocated there.

Photo of Nelson Island

Camp Rented

Internment camps were not unique to Trinidad and also existed in Bonaire, Cuba, Curacao, Jamaica, Martinique, and Suriname during WWII (Cwik, 2017). In Trinidad, they were instructed to treat the internees “firmly but fairly” whereby “no member of the staff will be permitted to adopt any aggressive or bullying manner towards them” (de Verteuil 165, 2014). At Camp Rented, the internees were reasonably fed considering the war rations, they were allowed listen to music, read and acquire books, and listen to radio stations such as the BBC to follow the war’s progress. Despite these allowances, Camp Rented was basically a prison camp where internees were subject to inspections and constantly monitored. At its peak the camp is estimated to have had a population of over 1000 refugees (de Verteuil 2014). There are accounts of internees escaping, romantic meetings happening, and some were allowed to attend school.

The last Jews were released in January 1944 and Camp Rented finally closed. The internees were subject to conditions upon release. Some internees were required to report to the nearest police station while others had restrictions on owning any form of transport or could not be on the road during the hours of 8pm to 6am. Some also had to avoid areas where military personnel frequented (de Verteuil 2014). Camp Rented is now recorded in books, but no physical structure remains today.

Photo of the Bet-Olam Jewish section, Mucurapo Cemetery, Port-of-Spain. Photo by Kara Roopsingh

Bet-Olam Jewish section, Mucurapo Cemetery

While many refugees stayed in the Caribbean and made a new life in the region, After the war many refugees used the islands as a temporary stepping-stone and migrated to the USA or Canada but, a few stayed in the Caribbean, assimilated and made a new life in the region. Some became business owners, tailors, lawyers and they set up synagogue for prayer and had community activities. The Mucurapo cemetery, is a poignant reminder of this neglected chapter of history (Newman 2019). One only has to read the inscriptions on the gravestones of the Bet-Olam Jewish section which list the countries of birth as Romania, Germany, Austro-Hungary, Transylvania etc, all outside of Trinidad. The Hebrew writing, Jewish symbols and inscriptions like “holocaust survivor” connect every visitor of the cemetery to the global story of the refugee crisis of World War 2 and how it arrived on the shores of our small island. The Religious Committee of the Jewish Association purchased and consecrated a section of the Mucurapo Cemetery in 1930 and the first burial took place in 1940. De Verteuil’s (229, 2014) book has a record of the burials up to 2002 of the Bet-Olam (House of the World) Jewish section.

Considered to be the “custodian of the refugee memory” (Newman 2001), Mr Hans Stecher’s grave can also be found at the Mucurapo Cemetery. Hans Stecher, a teenager at the time, was one of the Camp Rented internees who was allowed to leave the camp daily to attend Queen’s Royal College. Mr Stecher’s enduring legacy is well recorded in his memoir as Trinidad’s last surviving World War 2 Jewish refugee who stayed in Trinidad after the war ended and went on to become a successful businessman locally. Mr. Stecher kept the story of the Jewish refugee experience alive. Hepassed away in 2014 at the age of 90 and is best known for his luxury gift store Stechers on Frederick Street, Port of Spain.

Photo of the graves of Hans Stecher and Sheila Stecher with the Jewish tradition of placing stones at graves. Bet-Olam Jewish section, Mucurapo Cemetery, Port-of-Spain. Photo by Kara Roopsingh

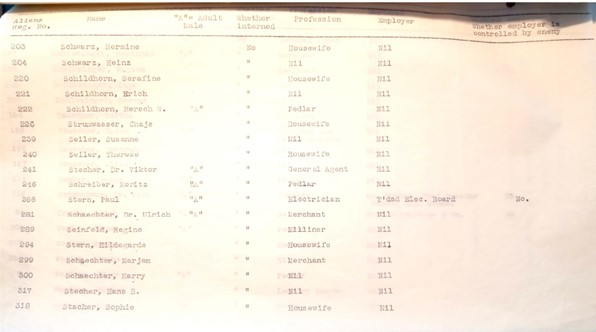

List of refugees at Camp Rented record from the UK Archives showing Hans B. Stecher as internee #317.

Close up photo of the gravestone of Victor and Carol Stecher showing Hewbrew inscriptions and “Holocaust survivor” with the Jewish tradition of placing stones at the graves. Bet-Olam Jewish section, Mucurapo Cemetery, Port-of-Spain. Photo by Kara Roopsingh

The Jewish legacy

The legacy of the Jewish community in is “woven into the fabric of contemporary Trinidad: avenues and streets are named after Albert Einstein and the Zionist leader Theodore Herzl, and stores in downtown Port of Spain still bear the names of their Jewish founders, among them the Yufe family, whose name is etched into the pavement in front of their many fabric stores” (Newman, 2001). In the 1940s an area called New Yalta was developed by a Jewish owner, Averboukh, with street-names named after Jewish heroes. The area still exists today (Anthony 2009). To practice their faith, a house was rented for use as a synagogue in 1939. There is no longer a synagogue in Trinidad and Camp Rented is no longer around, but you can still visit Nelson Island Heritage Site https://nationaltrust.tt/heritage-sites/nelson-island/ or the Mucurapo Cemetery as sites of remembrance. The two internment islands of Nelson Island and Caledonia Island are under the care of the National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago and remain sites of remembrance where visitors can hear about the World War II and the history of the internment camps for these ‘enemy aliens’.

Scan of photo showing house facing the Southeast corner of Victoria Square that was leased from 1939 for many years and used as a synagogue by the Jewish community until the synagogue was transferred to a building on Park Street. Source: de Verteuil 2014.

There are a few important stories recorded from this time. An autobiographic film done by Su Goldfish called The Last Goldfish https://www.thelastgoldfish.com/trailer explores the life of her father fleeing the terrors of Kristallnacht to the only place that would let him in without a visa, Trinidad. Stories like this put into perspective the global nature of wars and genocide and Trinidad’s role as a safe haven for hundreds of refugees. I highly recommend this film to all Trinis who wish to explore this side of their heritage.

The United Nations General Assembly designated January 27th—the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau — as the International Holocaust Remembrance Day. “The UN urges us annually to honour the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust in Europe, and millions of other victims of Nazism in the 1930s and 40s, and to develop educational programs to help prevent future genocides.”(Lane 2022) People are urged to never forget through a variety of ceremonies, solemn remembrance acts and educational campaigns. https://www.un.org/en/outreach-programme-holocaust/2023-theme-holocaust-remembrance-and-education-home-and-belonging

Sadly, these issues are not all in the past, the UNHCR estimates that 89.3 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced at the end of 2021 as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order. While visiting these sites and enjoying the process of learning about the history, we can never forget the atrocities humanity faces both here and abroad.

“It is the obligation of every person born in a safer room to open the door when someone in danger knocks.”

— Dina Nayeri

Author: Kara Roopsingh, Senior Heritage Preservation and Research Officer.

About the author: Kara Roopsingh is the Senior Heritage Preservation and Research Officer at the National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago. She is a tree-hugger-ocean-lover but has a passion for old bricks, historic architecture and shared memories. She enjoys uncovering the stories behind old buildings, natural spaces, communities, and special places.

References:

Anthony, Michael. (2009) Towns and Villages of Trinidad and Tobago. Port of Spain: Zenith Printing Services Limited.

Cwick, Christian and Muth, Verena (2017) European Refugees in the Wider Caribbean in the Context of World War 2, in World War 2 and the Caribbean eds Karen E. Eccles and Debbie McCollen. The University of the West Indies Press; Jamaica.

DeVerteuil, A. (2005). The Western Isles of Trinidad . Port-of-Spain: Paria Publishing.

DeVerteuil, A. (2014). Edward Lanza Jospeh and the Jews in Trinidad . Port-of-Spain: Litho Press.

Lane, Lena (2022) In Honor Of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Sites To ‘Never Forget’. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lealane/2022/01/24/in-honor-of-international-holocaust–remembrance-day-sites-to-never-forget/?sh=6b2304cb246f

Morris, A.J. (2019) From Port to Prison: A Study of the Layered History of “The Five Islands” 1797 – 1970.

Newman, Joanna (2001) Exiled to paradise. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2001/aug/11/socialsciences.highereducation

Siegel, A. (2003). An Unintended Haven: The Jews in Trinidad 1937-2003. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Sherwood, Harriet (2019) International Day of Commemoration in memory of the victims of the Holocaust https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/07/trinidad-cemetery-jewish-refugees-holocaust-forgotten-story

https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html (Accessed on 25/01/2022)