By Karishma Nanhu

History of the Divali Nagar Site

Location: Narsaloo Ramaya Marg Road, Chaguanas

“Divali was introduced to Trinidad and Tobago 175 years ago, by indentured Indian labourers. Since then the number of individuals actively celebrating the festival has increased, the nature of the celebration has evolved and today Divali is not only a national holiday but also one of the biggest religious/cultural celebrations in our country. From 1845 to present day, this Hindu religious festival has undergone many changes; it has moved from the private domain to the public sphere, it has embraced Trinbagonians of various religious and ethnic groups and persons of all social standings”. (Mahase, 2020)

The Divali Nagar is a celebration of Divali, the Hindu festival of lights. The term ‘Nagar’ means city. It takes place every year, nine nights prior to Divali, ending on the night before Divali. It is the largest Divali celebration outside of India in one space. The Divali Nagar is organized and run by the National Council for Indian Culture (NCIC). The Nagar has an annual theme which is taken from different aspects of Hinduism. There are educational activities and cultural performances by Trinidadians, from the wider Indian Diaspora and from India. A range of items are sold at the Divali Nagar including Indian clothing, Divali supplies and Indian and Indo-Trinidadian foods. It is a very popular food spot for Trinidadians, many of whom simply visit to partake in the notorious pepper roti.

Today the Divali Nagar is a well-known, even taken for granted part of Trinidad’s culture. It is now a huge local tourism event which attracted approximately 150,000 people over the nine-night period in 2019 (NCIC TT, Facebook, 2020). Indeed, Mr. Deokinanan Sharma, President of the NCIC believes that the Divali Nagar has immense potential for niche tourism and should be marketed to the diaspora as such (Sharma, 2020). Currently, Trinbagonians from all walks of life visit the Divali Nagar for numerous reasons. The importance of the site is underscored by its inclusion on the Heritage Asset Inventory of the National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago. However, the Nagar did not always have this national significance. The establishment of the Divali Nagar is set within the context of the Indian diaspora in Trinidad and Tobago carving out a space for themselves in the national arena and articulating Indo-Trinidadian identity within the national identity and consciousness. This blog looks at the history and significance of the Divali Nagar.

The NCIC and Divali Nagar

When Trinidad and Tobago achieved independence in 1962, there was a surge of patriotism, and a drive to express a national culture and a national identity. This stimulus is what encouraged the formation of the National Council for Indian Music and Drama (NCIMD) in 1964. The idea for the NCIMD was the product of collaborative effort of several people: Bisram Gopie, Narsaloo Ramaya, Moean Mohammed, Farzan Ali and Baldeo Maharaj. According to Professor Brinsley Samaroo (2015), the formation of the organization which arose out of the spirit of independence ushered a “…renaissance of Indo-Caribbean culture, which had seriously lapsed under colonial rule”. This push to affirm Indo-Trinidadian identity was driven further by the Black Power Movement of 1970 (Samaroo, 2014). The NCIMD was renamed the NCIC in 1970, the same year that its new president was elected, Mr. Hansley Hanoomansingh.

Mr. Hanoomansingh would later play a key role in the establishment of the Nagar. Divali was recognized as a national holiday in Trinidad and Tobago1966. Twenty years later, in 1986, the concept of the Divali Nagar was born. It was the brainchild of the Mr. Hanoomansingh. The idea was to have a place where the national community could participate in Divali. Prior to the establishment of the Nagar, Divali was celebrated mainly at private homes and in villages with a strong Hindu presence. Indeed, prior to 1966 Divali celebrations were limited to mainly religious functions, which were semi-public, and the attendees were mainly Indo-Trinidadians (Gooptar, 2015). After 1966, and especially after the 1975 with the influx of oil dollars, Divali became a more public affair. The oil boom led to everyday citizens have more disposable incomes, which had an impact on spending on festivals generally.

Picture of the First Divali Nagar in 1986

Source: Gooptar, Primnath. (2015). Cultural Persistence: 50 Years of the National Council of Indian Culture, 1964-2014.

The establishment of the Divali Nagar forever changed the celebration of Divali in Trinidad and Tobago. Now it became twofold: the private and communal celebrations took place but the Divali Nagar became a national affair. The establishment of the Nagar did not come without pushback. According to Gooptar (2015) there were members of the Hindu population who did not approve of such a public celebration of Divali. There was also criticism that the NCIC was a cultural organization and should not branch into the religious arena.

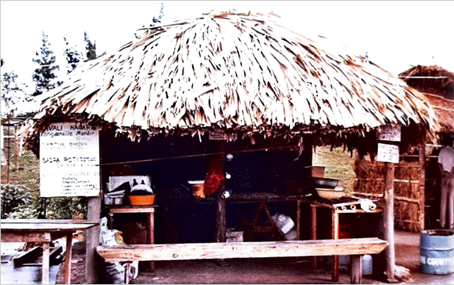

Picture of a traditional kitchen at the first Divali Nagar, 1986

Source: Gooptar, Primnath. (2015). Cultural Persistence: 50 Years of the National Council of Indian Culture, 1964-2014.

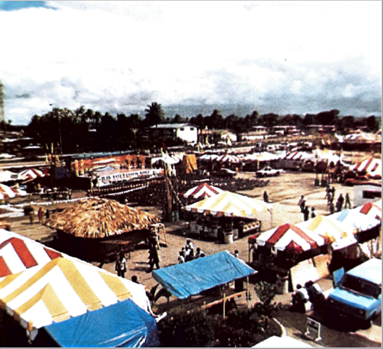

The first Divali Nagar in 1986 took place with the help of various Hindu organizations and countless volunteers. It was held at Mind Centre Mall, Chaguanas. The first Divali Nagar in 1986 was especially memorable, as it was not simply a display of performing arts, indeed it had deeper cultural meaning to see Indian way of life on display on such a large scale. The NCIC expected 10,000 people to visit. However, on the first night 23,000 people visited the Divali Nagar, which at the point in time was the largest celebration of the Indian Diaspora in Trinidad. This was “the fillip needed to push Indian Culture in the forefront of cultural activities in T&T” (Bhimull, 2014).

Divali Nagar was held at the Mid Centre Mall carpark until 1989.

Picture of the First Divali Nagar in 1986

Source: Gooptar, Primnath. (2015). Cultural Persistence: 50 Years of the National Council of Indian Culture, 1964-2014

Picture of Divali Nagar, 1988

Source: Gooptar, Primnath. (2015). Cultural Persistence: 50 Years of the National Council of Indian Culture, 1964-2014

The Divali Nagar Site

Divali Nagar got a new home in 1991 at the Narsaloo Ramaya Marg Road, Chaguanas. It can be seen from the Uriah Butler Highway. The NAR Government granted land to the NCIC to host the Divali Nagar. The two main politicians responsible for this were Professor Brisnsley Samaroo and Mr Winston Dookeran. The NCIC was granted fifteen acres of land previously owned by Caroni 1975 Ltd., for the home of the Divali Nagar. The land that was donated was used for growing sugarcane, it flooded frequently in the rainy season and it had to be drained and filled. In 1991 the Divali Nagar was held at the present location for the first time.

The significance of the Nagar is lost without explaining what existed before. There was nothing like the Nagar to compare it to. According to Mr. Deokinanan Sharma, President of the NCIC, prior to establishment of the Nagar, Indo-Trinidadian culture was stagnant, and it was not recognized nationally. Divali Nagar elevated Indo-Trinidadian culture and put it on the map (Sharma, 2020). Indian culture was not portrayed on such a large scale which mean national attention. Mr Hanoomansingh is therefore recognized as a pioneer who achieved recognition of Indian culture in wider Trinidad and Tobago. The Divali Nagar site is used for several purposes ranging from academic conferences and lectures, weddings, religious functions and other social activities.

“Today Divali Nagar is far more than a centre for the annual celebration of the Deya Divali. Since its inception, it has become a teerath (a place of pilgrimage) for the persons from Martinique, Guadeloupe, Jamaica, Guyana, Suriname, Grenada, St Lucia and St Vincent and the Diaspora settled in the USA, Canada, UK and Holland.” (Samaroo, 2015)

This year due to COVID-19 Restrictions the NCIC is having a Divali Nagar media presentation on television and social media entitled “Yaadein: The Memories of a Lifetime”.

Historical Treasures at Divali Nagar:

- The only remaining Train that is intact!

While there are a few remaining engines in Trinidad (like Railway Engine No. 11) the train at Divali Nagar is considered the only Train because the engine is connected to the taskar which carried canes.

In October 2019 the 4th Tunapuna Scout Group together the National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago did a clean-up of the last remaining Train in T&T.

- One of the oldest known surviving Ramcharitramanas (Tulsi Ramayan) texts brought from India by Indentured Immigrants to Trinidad. There is an ongoing drive to collect historical artefacts the Heritage Centre (established in 2016) at the Divali Nagar.

You can visit the National Trust’s website to find out more about our Heritage Asset Inventory, Learning Resources, Trusted Articles, Tours and more.

Sources:

Secondary:

Bhimull, Visham. (2014). History of the Divali Nagar. https://ncictt.com/2019/10/history-of-divali-nagar/

Gooptar, Primnath. (2015). Cultural Persistence: 50 Years of the National Council of Indian Culture, 1964-2014. Chaguanas: NCIC Heritage Publications.

National Council of Indian Culture. History. https://ncictt.com/history/

NCIC TT Facebook, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/NCICTT/

Samaroo, Brinsley. (2015). Foreword of Cultural Persistence: 50 Years of the National Council of Indian Culture, 1964-2014. Chaguanas: NCIC Heritage Publications.

Samaroo, Brinsley. (2014). The February Revolution (1970) as a Catalyst for Change in Trinidad and Tobago. In Quinn, K. (Ed.), Black Power in the Caribbean. University Press of Florida.

Primary:

Mr. Deokinanan Sharma, personal interview, 09/11/2020.

Dr. Mahase, Radica, personal interview, 09/11/20 20.