Written by Maya Doyle

The greatest show on earth has been celebrated for the last two centuries in Trinidad and Tobago. Carnival, began as a French celebration started in 1783, directly influenced by the mass immigration of French planters from neighbouring islands. The cultural atmosphere was dynamically transformed by the presence of such a large French population with the dominant group setting the precedent for social norms. Carnival was celebrated from Christmas to Ash Wednesday.

Carnival festivities usually lasted from Christmas to Ash Wednesday during which they would host concerts, balls, dinners hunting parties and fetes champetres throughout the season. Carnival was ultimately a parade of the elite in society adorned in elegant wardrobe and costume. Priests and friars, grooms and postilions, Swiss damsels, French marquis, English noblemen and noblewomen were some of the many costumes worn by the upper class.

Bands were formed of participating upper class men, ironically, dressed in ‘negres jardin’ or garden labourers costumes, carrying torches and drums, depicting the enslaved Africans performing the Cannes Brulees (burning of canes) or Canboulay. Fires on the plantations, started by the enslaved Africans or not, were extinguished through a certain practice. The enslaved were herded into gangs and marched into the fields, carrying flambeaux to dowse the fires, and this was subsequently called Canboulay. The enslaved Africans were unwelcome and prohibited from the Carnival festivities, but they were attentive spectators.

Upon the Abolition of slavery in 1833, Carnival in Trinidad was stained with the intervention of the freed Africans, no longer a blue blood studded event. The classical and poised procession was transformed into a high-spirited and crowded festival, where the freed Africans expressed themselves in costume. Costumes, such as one where a character was covered in chains and padlocks, thrown to the ground, mocked and beaten, were used by the Africans to portray the horror of slavery. Others dressed in costumes that mocked the upper-classes. The participation of the formerly enslaved abruptly tarnished the event in the minds of the bourgeoisie.

The Africans formed stick-fighting bands where they would mimic Canboulay. The Canboulay bands were described as ‘an unremitting uproar, yelling, drumming and blowing of horns’. The performers would come out at midnight, carrying sticks, flambeaux and drums in hand, whilst singing songs and marching to the beat of the drumming. The fighting between the stick fighters was violent and the wooden infrastructure in the vicinity where they performed was also in danger of combusting as they carried their lit torches while performing.

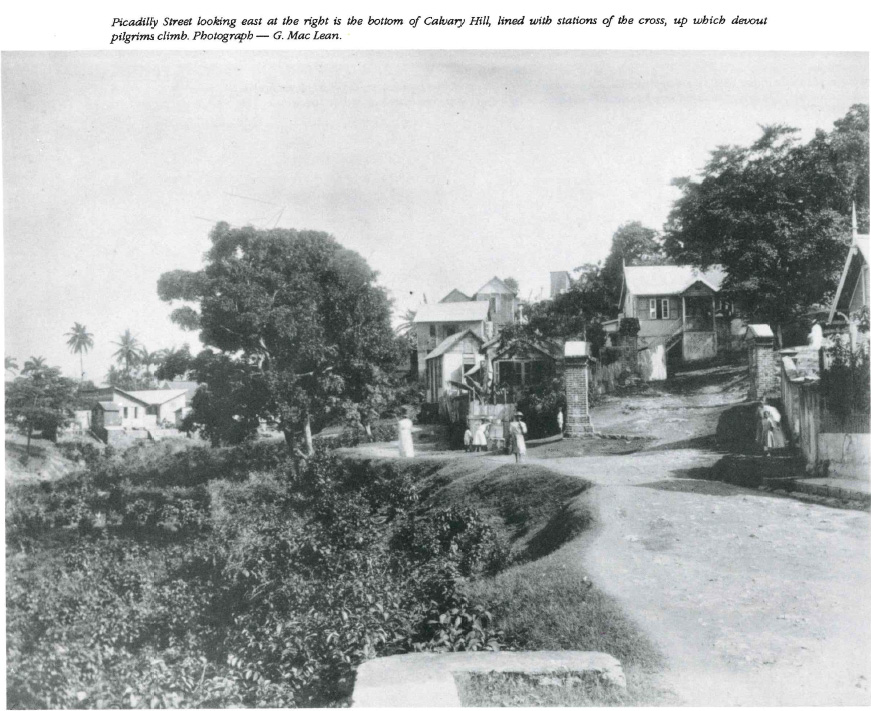

The outcry of the upper class society against the “Jamette Carnival”, as they called it, was met with attempts of suppression of the festival by the armed forces. However, it was only until Captain Arthur Baker, assumed his post as Chief of Police, that a notable effect was made. In 1881, Captain Baker, along with his police force, faced off against the Canboulay bands on Piccadilly Street, in battle which would forever etch a place in Carnival history.

In the battle, Captain Baker and his one hundred and fifty police officers atop horses, armed with batons, acted to expunge the Canboulay bands once they reached Duke Street. Bottles, sticks and stones were thrown in retaliation by the Canboulay bands. Thirty-eight officers of the police force and many members of the Canboulay bands were injured. The riots eventually reached such a heightened level that the Governor confined the police to their barracks. Following the riot, the French Creoles supported the lower class blacks expressing their disgust for the excessive and disrespectful methods of the police force against the celebration of Carnival, which was a traditional and culturally significant event to the French.

In late 1881, a proclamation was made, allowing Carnival of 1882 to proceed with stipulations stating, that lit torches were only allowed during the hours of midnight on Carnival Sunday to five am on Carnival Monday, only in open spaces, such as the Queen’s Park Savannah. This celebration began at dawn, and later became to be known as J’ouvert (Jour Ouvert – the day opens).

Carnival in the 1890’s improved as a result of the economic development merchants experienced during the season. The introduction of competitions for best dressed band or individual brought forward multiple characters such as Wild Indians, Robbers, Clowns, Devils and other traditional masqueraders. As Carnival, lived on, the reverence for the Canboulay riots as a significant moment in Carnival history constructed a subsequent re-enactment of the riots in Trinidad. The Canboulay Riots re-enactment is annually performed on Carnival Friday at 3am at Piccadilly Street (Piccadilly Greens), and many citizens gather to see this history.

Alongside the re-enactment of the Canboulay Riots, a piece of tangible heritage can be witnessed on Piccadilly Street. The house at 58, Piccadilly Street in Eastern Port of Spain, was built in 1920 by Henry and Enid Figari. Located alongside the East Dry River, the house served as a residential home for seven children as they attended school whilst parents Enid and Henry Figari provided for their family with their management of a cocoa business in Moruga.

The house emulates the architectural style of the famous ‘Gingerbread House’ built in 1904 by Edward Bowen and carries notes of influence of George Brown, the Scottish architect responsible for the construction and design of various famous buildings in Port of Spain. The house is steeped in decorative fretwork, steep pitched gables and an ornate covered walkway which depicts the popular style of houses in Trinidad at the time.

Some aspects of the tangible and intangible history and culture of Trinidad collide on Piccadilly Street. Witnessing the vivid and animated events of the past at the Canboulay Riots on Carnival Friday, whilst being able to regard a picturesque, protected structure, is an opportunity citizens and visitors to Trinidad and Tobago can enjoy. The rich historical events of Trinidad spill over onto one another on this famous street and the festival of Carnival grants an opportune time to experience this celebration of our past.

Text References

Besson Gérard, and Bridget Brereton. The Book of Trinidad. Paria Pub., 2010.

Liverpool, Hollis. Rituals of Power & Rebellion: the Carnival Tradition in Trinidad & Tobago, 1863-1962. Research Associates School Times, 2001.

Smith, Angela. Steel Drums and Steelbands: a History. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Image References

Besson Gérard, and Bridget Brereton. The Book of Trinidad. Paria Pub., 2010.

National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago – https://nationaltrust.tt/